MABO REVISITED by Paul Dillon is a penetrating and enlightening analysis of the High Court, Mabo No. 2 decision. The book is informative and useful in portraying a clear historical picture of the events leading up to Mabo No. 2 and the decision itself. Available online as a Ebook from Amazon Kindle @ US$6.50 or a paperback from Ebay Australia @ $19.99

Author Archives: Paul

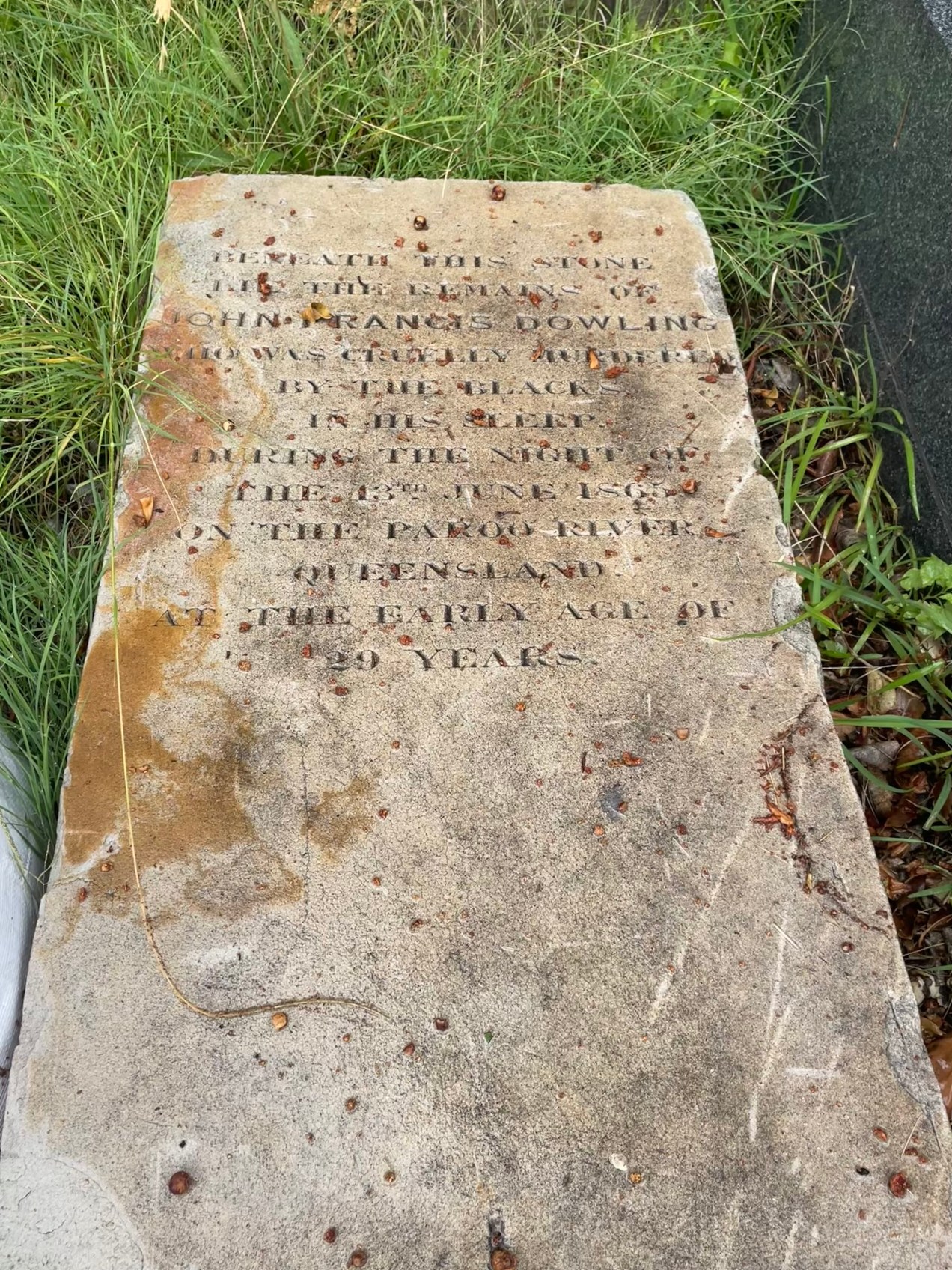

John Francis Dowling – An Update

In 2019, I published The Murder of John Francis Dowling and the Massacre of 300 Aborigines. By a letter dated 14 March 2025, I was informed by the minister of the Anglican parish of St Jude’s Randwick, Sydney, which has a remarkable historic cemetery behind the church, that a great sandstone slab had been discovered. It was the gravestone of a John Francis Dowling.

The inscription states: Beneath this stone lie the remains of John Francis Dowling who was cruelly murdered by the Blacks in his sleep during the night of the 13th June 1865 on the Paroo River Queensland at the early age of 29 years.

The tombstone inscription is consistent with Dowling’s death certificate, which is not surprising, and is an additional piece of physical evidence that John Dowling was killed on the Paroo River and not the Bulloo River. On 5 July 2017, the Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930 website was launched. The ABC proclaimed without critically examining the site that “Now a landmark project mapping those massacres has hit a sobering point — 250 sites have been documented across almost every state and territory.” In 2019, the site declared with great authority that between 1 Jan 1865 and 31 Dec 1865 at Thouringowa Waterhole, Bulloo River, 300 Aboriginals were killed: “Following the killing of Ardoch station owner John Dowling (on the Bulloo River), his brother Vincent led a posse of settlers including EO Hobkirk and set out in revenge and found the Kullila camped on the eastern side of the river and chased them towards the Grey Range, shooting them down as they ran. McKellar says the posse was led by the native police and that 300 were killed.”

I my book of 2019, I conclusively proved that John Dowling was murdered on the Paroo River by the Blacks and that there was no massacre of Blacks on the Bulloo River by Vincent Dowling or any other person or persons. The Massacre website of 2025, now records that between 1 Jan 1865 and 31 Dec 1865 at Thouringowa Waterhole, Bulloo River, 30 Aboriginals were killed. That is a 90% reduction. No explanation is given for the reduction. My book of 2019 is now cited in the sources. However, the Massacre website still persists with the allegation that a massacre occurred at the hands of Settler(s), Stockmen/Drover(s).

The tombstone is beyond doubt a relic to rival any historic gravestone to be found within the churchyards of England. It is a find to be treasured and preserved for future generation of Australians.

The Murder of John Francis Dowling and the Massacre of 300 Aborigines by Paul Dillon, ISBN 9781925826500 Paperback, 124 pages, $29.95 available from Connor Court Publishing, Brisbane.

Review of “Mabo Revisited”

The work excels in its rigorous examination of the High Court’s decision-making process, questioning the constitutional legitimacy of extending native title rights to mainland Aboriginals. This scrutiny adds an original and provocative viewpoint to the ongoing discourse about the judicial interpretation of indigenous land rights in Australia. Additionally, the book’s thorough historical context helps frame the Mabo decision within a broader socio-political narrative, offering critical insights into often-overlooked judicial dynamics.

The core argument centres on the proposition that the High Court delivered an advisory opinion rather than a binding judgment, thereby overstepping constitutional limits.

The intersecting domains of constitutional law and indigenous rights form the robust foundation of this book. However, the discourse presented here also touches on ethical considerations, specifically concerning the judiciary’s role in advocating social justice versus adhering to procedural restraints. The narrative implicitly invites debate about the evolving role of judicial bodies in shaping societal norms, a matter of keen interest in broader legal and ethical contexts.

Summary Assessment

“Mabo Revisited” advances an intellectually stimulating conversation about the constitutional ramifications of landmark legal decisions in Australia. While its core thesis challenges prevailing judicial norms, its broader implications call for a re-evaluation of judicial activism and its societal impacts. This work is a compelling read for those interested in constitutional law, judicial processes, and indigenous land rights, contributing to an ongoing examination of how law adapts to societal needs.

In closing, while the arguments presented are indeed contentious, they provoke necessary discourse on the judiciary’s role in modern governance. Such discussions may ultimately lead to a more nuanced understanding of the balance between judicial intervention and restraint.

Mabo Revisited High Court Shenanigans, Paperback, Perfect Bound, A5, 129 pages, ISBN: 9780994638182. Available online as a Ebook from Amazon Kindle @ US$6.50 or a paperback from Ebay Australia @ $19.99.

MABO No. 2 – 1992.

Chapter 5 ― High Court of Australia

The Constitution of Australia is based broadly on the principle of ‘responsible government’ and the separation of powers doctrine, where the powers of the Constitution are shared or divided amongst the Parliament, the Executive and the Judiciary. The High Court of Australia is the principal or premier court of Australia and determines, among other things, issues of constitutional law and the laws of Australia.

In re Judiciary and Navigation Acts, the High Court held that the High Court cannot give advisory opinions.[1] It has no power or jurisdiction to determine abstract questions of law without the right or duty of any body or person being involved. The High Court’s constitutional function, which is judicial, is to give relief inter partes or ex parte and must involve some right or privilege or protection given by law, or the prevention, redress or punishment of some act inhibited by law.[2]

In North Ganalanja Aboriginal Corporation and Anor for and on Behalf of the Waanyi People v The State of Queensland and Ors, the question of advisory opinions by the High Court came up for determination.[3]

McHugh J. in considering the granting of special leave on the pastoral issue, said:

39. Obviously, the Court could not grant special leave to decide the pastoral lease point if it concluded that special leave to appeal should be granted on the procedural issue on the ground that the Tribunal erred in refusing the application of the Waanyi People. Upon granting leave and allowing the appeal on the s 63 procedural issue, the only order that the Court could make was the one that it did make. That is to say, that the judgment of the Federal Court be set aside, that the appeal to that Court be allowed and the Registrar be directed to accept the application of the Waanyi People. If the Court had also granted special leave and purported to give an opinion on the extinguishment issue, it would have given an opinion which it had no constitutional jurisdiction to give. The opinion of the Court would have been an advisory opinion. It would have been giving an opinion on a matter that did not arise because, ex hypothesi, the order of the Court on the procedural issue would direct the Tribunal to accept the application. The Constitution gives this Court no jurisdiction to give advisory opinions in either its original or its appellate jurisdiction.

Kirby J. held on the question of the limits of advisory opinions:

42. I cannot agree for a moment with the proposition that the determination by the Court of the “pastoral lease question” would have amounted to the impermissible provision of an advisory opinion, forbidden by the Constitution and the Court’s past authority. Nobody suggested during argument that it would be so. In my opinion this is because, manifestly, it would not.

43. The current rather narrow state of authority on the Court’s original jurisdiction to provide advisory opinions may one day require reconsideration as the Court adapts its process to a modern understanding of its constitutional and judicial functions. Since In re Judiciary and Navigation Acts was decided in 1921 there has been a substantial development in the understanding of what the judiciary in Australia may properly do in discharging its proper functions. For example, the scope of the availability of the beneficial remedy of a declaration, to deal with an apprehended threat of invasion of rights, has expanded greatly, overcoming in the process some of the same resistance as lay behind the refusal to provide advisory opinions. The judicial function is not frozen in time. This Court should remain alert to developments in judicial procedures which further, in proper ways, the defence of the rule of law. So far as is compatible with the judicial function, courts should endeavour to be constructive and useful to parties in dispute. If courts do not adopt this attitude, those parties will look to other means, rely on their power or be left unrequited by their expensive visits to the courts.

Of course, the “pastoral lease question” was settled by Wik Peoples v Queensland (“Pastoral Leases case”).[4]

The plaintiffs litigated Mabo No. 2 by alleging that since time immemorial their ancestors, and, thus, they, had owned and had rights in particular areas of land on the Murray Islands, the surrounding sea and seabed and reefs in accordance with their laws, customs, traditions and practices and that the annexation of the islands by Queensland in 1879 was subject to the rights of their predecessors in title. They sought various declarations to that effect. Importantly, the plaintiffs sought declarations in respect of particular plots of land or with respect to the seabed, seas and fringing reefs allegedly owned by those individuals and their family groups—ultimately 36 blocks were claimed by Eddie Mabo, one by Dave Passi and four by James Rice.[5] Moynihan J observed that during the course of the hearing the pleadings (statement of claim, defences and replies) evolved through a number of editions. A final version was handed up to the High Court on 31 May 1991 with a further addition on 3 June 1991.[6]

Set out below are the statements by each Justice of the issue or matter before the court for determination:

Mason C.J. and McHugh J. made no specific comment.

Brennan J. The plaintiffs are members of the Meriam people. In this case, the legal rights of the members of the Meriam people to the land of the Murray Islands are in question.

Deane and Gaudron JJ. The issues raised by this case directly concern the entitlement, under the law of Queensland, of the Meriam people to their homelands in the Murray Islands.

Toohey J. 2. The plaintiffs claim that they or the Meriam people are, and have been since prior to annexation by the British Crown, entitled to the Islands: (a) as owners (b) as possessors (c) as occupiers or (d) as persons entitled to use and enjoy the Islands. The declarations now sought give primacy to the rights of the Meriam people rather than to those of the individual plaintiffs.

Dawson J: 3. The plaintiffs are Murray Islanders and members of the Meriam people. Each of them claims rights in specified parcels of land on the Murray Islands. The basis of their claims is, alternatively:

(a) their holding the land under traditional native title;

(b) their possessing usufructuary rights over the land; or

(c) their owning the land by way of customary title.

The observant reader will note that the Justices stated the issue before the court differently. Brennan, Deane and Gaudron JJ. stated the issue in the broadest of terms. Toohey J. stated that the issue had moved from the rights of the individual plaintiffs to the Meriam people. While Dawson J. stated the issue as pleaded by the plaintiffs.

The exercise of judicial power by the court is in the making of its orders, not the giving of its reasons.[7] On first reading the judgments of the Justices, one is struck by the polemical argument relating to mainland Aboriginals. Only after reading Dawson J’s judgment, which is straight up and down, does the reader realise that his reasons fit his decision like a glove, which was to refuse the declarations sought by the plaintiffs. The same cannot be said of Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and Toohey JJJJ. (Gang of Four).[8]

How were Mainland Aboriginals joined?

Brennan J.: 24. Nor can the circumstances which might be thought to differentiate the Murray Islands from other parts of Australia be invoked as an acceptable ground for distinguishing the entitlement of the Meriam people from the entitlement of other indigenous inhabitants to the use and enjoyment of their traditional lands. As we shall see, such a ground of distinction discriminates on the basis of race or ethnic origin for it denies the capacity of some categories of indigenous inhabitants to have any rights or interests in land. It will be necessary to consider presently the racial or ethnic basis of the law stated in earlier cases relating to the entitlement of indigenous people to land in settled colonies.

Deane and Gaudron JJ.: 1. …Those issues must, however, be addressed in the wider context of the common law of Australia. Their resolution requires a consideration of some fundamental questions relating to the rights, past and present, of Australian Aborigines in relation to lands on which they traditionally lived or live.

Toohey J.: 11. Before proceeding further, one more point should be noted. While this case concerns the Meriam people, the legal issues fall to be determined according to fundamental principles of common law and colonial constitutional law applicable throughout Australia. The Meriam people are in culturally significant ways different from the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, who in turn differ from each other. But, as will be seen, no basic distinction need be made, for the purposes of determining what interests exist in ancestral lands of indigenous peoples of Australia, between the Meriam people and those who occupied and occupy the Australian mainland. The relevant principles are the same.

The Gang of Four joined mainland Aboriginals without a factual basis, without reference to legal rules, or procedural grounds and, most definitely, without notice to interested parties.

In a discussion on the Mabo No. 2 decision, the following question was asked:

Do you think it was necessarily good law to extend the Mabo decision to the other parts of Australia when, in fact, it is not absolutely necessary to do so in order to find that the Meriam people had native title?

The learned professor replied,

Yes. That aspect of the decision has been subject to some criticism. My view on that is that it was essential for the High Court to make some statement of principle.[9]

Then he was asked a further question:

Granting what you have said about the need for the Court to consider the generality of the application of the Mabo decision to the mainland of Australia, would you care to express a view as to whether it was justified in pursuing that line in the absence of any representation from either Aboriginals or non‑Aboriginals from the mainland of Australia? It appears to me that the Court made that decision and that application in the total absence of any representation from persons greatly affected.

To which the learned professor replied,

In the Mabo decision, the High Court did not purport to decide any particular claim of native title in respect of any land other than the Murray Islands. What it did was declare certain principles; and that is a time‑honoured function of the courts in our constitutional system. It is a function that the English courts have been performing for at least four centuries, probably longer, and it is a function which our courts have been performing ever since European occupation of this country and the inheritance of English law.[10]

The replies by the learned professor confirmed (a) that the High Court had purported to make rulings on law relating to mainland Aboriginals and (b) that the High Court had the constitutional power to make declarations on certain principals of law when it felt the need. In Air Canada v Secretary of State for Trade, Lord Wilberforce observed: “[T]he task of the court is to do, and be seen to be doing, justice between the parties … There is no higher or additional duty to ascertain some independent truth.”[11]

My view of what the Gang of Four (Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and Toohey) did was to purport to give an advisory opinion on the issue of native title on mainland Australia. They had fallen victim to the Big Picture syndrome. Although the professor was wrong in saying the High Court has constitutional jurisdiction to give advisory opinions, he supports my analysis of what Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and Toohey (Gang of Four) were doing, which was unconstitutional.

I now turn to Mason C.J. and McHugh J. who said, 4. The formal order to be made by the Court accords with the declaration proposed by Brennan J. but is cast in a form which will not give rise to any possible implication affecting the status of land which is not the subject of the declaration in par.2 of the formal order.

The above statement by Mason C.J., in my view, confirms and reinforces my analysis of the judgments of Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and Toohey (Gang of Four) that they contained advisory opinions on the law relating to the settlement of mainland Australia and, therefore, should be dismissed as unconstitutional.

There is an important issue arising from this and that is, some might argue or suggest that, although the ratio decidendi of Mabo is very narrow, the judicial reasoning by the Gang of Four, in particular Brennan J., might be treated as obiter dicta and nevertheless remain authoritative regarding mainland Aboriginal land rights. If that part of the judgment which constitutes the advisory opinion is unconstitutional, then the reasoning can have no authoritative value. The historical narrative adopted by the Gang of Four is a tawdry example of the doxa of the Black Armband school in which an overlord is said to oppress the underdog with trickery, treachery and dishonesty dressed up as solemn principles of law, like discovery coupled with terra nullius and social Darwinism. The narrative is hearsay, not sworn testimony tested in a court of law according to the principles of due process and natural justice, where each party is represented by his chosen advocate.[12]

On the other hand, some commentators have viewed the inclusion of mainland Aboriginals in the judgments as a gross example of judicial overreaching. Judicial overreaching often equates with judicial law making. In common law jurisdictions, the theory is that the function of the court is to make declaratory judgments, reaffirming pre-existing customs or case law. However, an often-quoted criticism of the common law is that it is judge made law. On occasion, critics have gone a step further and labelled some judgments as clear examples of the judiciary legislative function.

This idea of the High Court in Mabo No. 2 overstepping the boundaries of the declaratory theory of strict and complete legalism is a wonderful cover or red herring. It is a fertile area of constant controversy amongst academics, who make a living from the debate. I refer the reader to Michael Kirby’s article The Politics of Mabo for a discussion on how the High Court was simply updating the common law of Australia to reflect modern concepts of social justice.[13] From Kirby’s judgment in North Ganalanja Aboriginal Corporation and Anor for and on Behalf of the Waanyi People v The State of Queensland and Ors above, the reader can deduce that Kirby is gung-ho when it comes to moving away from the strict theory of judicial restraint to the new policy of judicial creativity. Mabo No. 2 is a wonderful illustration of the political power and the lack of accountability of the High Court, which is often concealed from the public.

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? (Who will guard the guardians?) That section or part of the judgments of Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and Toohey (Gang of Four) relating to mainland Aboriginals might be labelled a Noble Lie – certainly, the narrative outlined by the Gang of Four relating to the treatment of mainland Aboriginals is. The overwhelming failure of full blood Aboriginals to thrive and prosper under white settlement has confounded many Australians from the first day Arthur Phillip stepped ashore. The reaction or empathy to this collapse of tribal society has ranged across a wide spectrum to the extreme view that their situation is one of national tragedy reflecting very badly on the national ethos. That position is taken by those suffering from the delusion of historical revisionism which includes most minorities whether indigenous, ethnic, sexual, political, religious etc. and, of course, leftwing groups whether political, academic, feminists, environmentalists, journalists, social, etc.

Intervention by Attorneys-General.[14]

The Australian Law Reform Commission recommended that s 78A of the Judiciary Act be amended to provide for intervention by the Attorney-General of the Commonwealth and the Attorney-General of each State and Territory as follows:

The section should be amended to confer on each Attorney-General a right to intervene in non-constitutional matters that raise an important question affecting the public interest in the jurisdiction represented by that Attorney-General. The court should be given a power to direct whether the right of intervention shall be exercised by the presentation of written submissions, oral argument, or both.[15]

Although the ALRC made no mention of Mabo No. 2, but given the uproar the decision caused, perhaps, the recommendation seems reasonable.

Mabo Revisited Paperback, Perfect Bound, A5, 129 pages, ISBN: 9780994638182, Price: $19.99, available from Ebay Australia or Amazon Kindle @ US$6.50.

[1] [1921] HCA 20; 29 CLR 257.

[2] See Final Report of the Constitutional Commission 1988, PP no. 229 of 1988, Vol. 1, pp 414-417.

[3] [1996] HCA 2; (1996) 185 CLR 595 8 February 1996.

[4] [1996] HCA 40; (1996) 187 CLR 1; (1996) 141 ALR 129; (1996) 71 ALJR 173 (23 December 1996).

[5] White, The Honourable Margaret AO — “Mabo v State of Queensland (No 2): a personal recollection, (QSC)” [2016] QldJSchol 31. See pp 71-72 above.

[6] See appendix 20 & 21, A Mabo Memoir: Islan Kustom to Native Title, B Keon-Cohen 2013, Zemic Press p 506.

[7] Driclad Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1968) 121 CLR 45, 64 (Barwick CJ and Kitto J).

[8] The Gang of Four was a Maoist political faction who came to prominence during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) for their excesses in the Cultural Revolution. The same might be said of Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and Toohey.

[9] Crommelin ″Mabo: The Decision and the Debate″ Papers on Parliament No. 22, February 1994.

[10] Crommelin ″Mabo: The Decision and the Debate″ Papers on Parliament No. 22, February 1994.

[11] [1983] 2 AC 394 at 438.

[12] By the end of this book, I will have demonstrated that the Gang of Four were committed converts to Henry Reynolds’ history of Australia and willing implemented his dogma disregarding constitutional safeguards and the judicial safeguards of due process.

[13] Michael Kirby, Source: The Australian Quarterly, Summer, 1993, Vol. 65, No. 4, The Politics of Mabo (Summer, 1993), pp. 66-81

[14] Re: S78B, Mabo & Ors v Queensland & Anor (B12/1982) (“Mabo Case”) – Volume 8 – Transcript Before Mason CJ [1991] HCASCF 19 (20 March 1991) pp 9-11. Peter Connolly CBE, QC, observed: “While not a mystery, it has not been apparent to most of us that the Commonwealth was at first a defendant, managed to extract itself from that position, and become an intervener, and ultimately made no submission to the court. In other words, the Commonwealth instead of defending the interests of Australians generally ran dead. There can be no doubt that it thereby accepted a share of responsibility for the outcome.” Weekend Australian, September 11-12, 1993, p 24.

[15] ALRC 92 The Judicial Power of the Commonwealth: A Review of the Judiciary Act 1903 and Related Legislation, 31 July 2001, Recommendation 14-1.

Mabo Revisited High Court Shenanigans, Paperback, Perfect Bound, A5, 129 pages, ISBN: 9780994638182, Price: $19.99, available from the InHouse Bookstore by Phone 07 3208 7576, and by Email publishing@inhouseprint.com.au or Ebay Australia.

MABO REVISITED

This book is a penetrating and enlightening analysis of the High Court, Mabo No. 2 decision. It is the only scholarly work written about colonial settler/Aboriginal contact with an honest and forthright approach to the source material. The creation of a hereditary native title over land within mainland Australia will, in time, become an unreasonable burden and a substantial interference with the land use of the dominate landholder.

The earlier reviews were flawed because the vast majority of commentators have been ill-informed intellectuals or one-dimensional ideologues trying to toe the Indigenous Industry’s code of political correctness. The Black Armband school has allowed political partisanship to override honest research and sound conclusions. They approach the historiography of Australian Colonial Settler Studies with a fixed ideological axiom of resistance to invasion. Their articles and publications encourage unity of thought in support of this axiom by stressing and interpreting the historical sources and material in a tendentious and selective manner.

An ill-disciplined and prodigal Indigenous industry of tax-funded agitators, propagandists, and cultural cringing white Jackey Jackeys has, for fifty years, levelled a continuous barrage of slanders and base calumnies against the settlement of Australia by white pioneers and explorers, ignoring the first-world standard of living now enjoyed. Australian taxpayer’s funds are bleeding out because of political cowardice in the face of the haemorrhage.

Mabo Revisited, Paperback, Perfect Bound, A5, 129 pages, ISBN: 9780994638182, Price: $19.99, is available on Ebay Australia and Amazon Books as a eBook.

MABO REVISITED

In the High Court of Australia, on 20 May 1982, Torres Strait Islanders Eddie Mabo, Dave Passi and James Rice sought declarations of ownership of land on Murray Islands based on their laws, customs, and traditions, notwithstanding, the annexation of the islands by Queensland in 1879.

This is a ground-breaking book exposing the unconstitutional acts of certain judges of the High Court in their deliberations and judgments in Mabo No. 2 v Queensland on 3 June 1992.

The Constitution of Australia gives the High Court no jurisdiction to give advisory opinions in either its original or its appellate jurisdiction (In re Judiciary and Navigation Acts, 29 CLR 257). The judgments of the Gang of Four on the alleged land rights of mainland Aboriginals were undoubtedly an unconstitutional proceeding.

The Gang of Four misled the Australian Parliament, resulting in the Native Title Act, No. 110, 1993 (Australia), being based on bad law.

Their unlawful and unconstitutional actions were: (1) in joining mainland Aboriginals, their actions were arbitrary and an abuse of discretion, and without the observance of the procedure required by law; (2) exceeding their constitutional and judicial function by delivering an advisory opinion; and (3) compounding their conduct by excluding the Australian people from the proceedings.

Mabo Revisited, Paperback, Perfect Bound, A5, 129 pages, ISBN: 9780994638182, Price: $19.99, is available on Ebay Australia and Amazon Books as a eBook.

Fraser Island Massacre – More fake history.

In 2022, I published FRASER ISLAND MASSACRE Vrai ou Faux, Connor Court Publishing Pty Ltd, Brisbane. In Chapter 4, The Massacre, I referred to the website, Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930.[1] The website, at Site List, identified a massacre on Fraser Island listing 100 Aboriginal people killed between 24 Dec 1851 and 3 Jan 1852. The sources quoted for the incident were:

Lauer, P 1977, ‘Report of a Preliminary Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Survey of Fraser Island’, in Lauer, P. (ed.), Fraser Island, Occasional Papers in Anthropology, no. 8, Anthropology Museum, University of Queensland, St Lucia; and Sydney Morning Herald, January 22, 1852 – https://trove.nla.gov.au/ newspaper/page/1509723.

The particulars of the incident were:

To ‘break up’ Aboriginal clans that had sought sanctuary on the island a punitive expedition of eleven days duration was lead (sic) by Commandant Frederick Walker with 24 troopers of native police along with Lt Marshall and Sgt Major Dolan and captain and crew of the schooner, Maragaret (sic) and Mary, all armed and sworn in as special constables… Aboriginal people were ‘driven into the sea, and kept there as long as daylight and life lasted’. Lauer estimates that 100 Aboriginal people were killed.

The website was updated in 2024.[2] The number of Aboriginal killed was reduced from 100 to 50; no explanation was given for this reduction. The sources quoted for the incident now included, Vic Collins, Handwritten Account of an Aboriginal Massacre at Teewah, 2000.[3]

The 2024 particulars of this incident relating to Collins were:

Some comparable details, such as the deputisation of colonists, the killings on the beach and victims driven into the water, suggest this may be the same, or related to a massacre written from oral history by Vic Collins. According to Vic Collins a massacre took place just to the south of K’Gari on the mainland at Teewah Beach, north of Noosa: ‘The convicts were given their freedom provided they donned a red uniform (Red Coats) to keep the blacks in order. Stationed at Maryborough word came of a tribe of blacks stealing sheep from Mannumbar Station (on their way bay from Bunya Mts) Noosa blacks were blamed. The Red Coats track them to Teewah Beach. They were ordered to ride out on the beach and shoot the men (single shot muzzle loaders) then use swords on the remainder which they did. But children took to the water, so the officer in charge ordered the red coats to ride their horeses into the surf and trample the children till they drowned.’ (Collins, 2000)

Anybody with a smidgeon of nous would recognise that adding Vic Collins’ fairy tale does not enhance the probity of the supporting material for the alleged Fraser Island massacre but suggests that the authors of the website are clutching at straws to shore up their ludicrous piece of drivel on the so-called Fraser Island massacre.

Please refer to FRASER ISLAND MASSACRE Vrai ou Faux available from sales@connorcourt.com

[1] Ryan, Lyndall; Richards, Jonathan; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Stephanie Gilbert; Anders, Robert J; Brown, Mark; Smith, Robyn; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack Colonial Frontier Massacres in Eastern Australia 1788 to 1930, v3.0, 2019. Newcastle: University of Newcastle, 2018, http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 (accessed 11/9/2021). Funded by ARC: DP 140100399.

[2] Stage 5.0, Ryan, Lyndall; Debenham, Jennifer; Pascoe, Bill; Smith, Robyn; Owen, Chris; Richards, Jonathan; Gilbert, Stephanie; Anders, Robert J; Usher, Kaine; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack; Brown, Mark; Craig, Hugh Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930 Newcastle: University of Newcastle, 2017-2024, https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres (accessed 16/03/2024).

[3] Handwritten, single page account of a massacre of Aboriginal people in the late 1800s on Teewah Beach on the Cooloola Coast. The account is written by Vic Collins and relays information that was told to him by his father, William Collins, who had arrived in the area in 1896. State Library of Queensland

SOUTH SEA ISLANDERS IN QUEENSLAND

Foreword By Geoffrey Blainey

South Sea Islanders in Queensland is one of the most controversial topics studied by Australian historians. It is entangled with the sister topic of racism. It is complicated because it involves labourers shipped to Australia, in the course of half a century, from some 80 different Pacific Islands. Here also is a vital strand in our nation’s political history, for it led to one of the few secession campaigns: the hope in the 1880s that coastal north Queensland would break away from Brisbane and form a seventh colony or state.

Almost everywhere in the world in the 19th century, sugar cane was a stronghold of coloured labour: the belief was universal that white men could not perform outdoors manual work in a very hot climate. As more and more sugar was produced in Australia, the heart of the sugar industry moved to the tropical coast of Queensland. To find the necessary labourers, ships visited an array of South West Pacific islands including New Guinea, Vanuatu and the Solomons. The recruiting was often brutal but often peaceful. If you read about this traffic and trade in such easily-found sources as Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Britannica, and then turn to Paul Dillon’s latest book, you will sometimes wonder whether you are reading about the same episode in history.

Dillon often sets out long documents which give readers an opportunity to learn more and more, and even to make up their mind. Thus, he challenges the prevailing view that these islanders were usually shipped home like sheep without any worthwhile gain. And yet here, without much comment, is a brief aside on a return voyage from Queensland in the ship Spunkie. Scores of the islanders had crammed into the ship’s hold a small mountain of luggage “some of them having as many as three and four large boxes of clothes, besides loose articles of furniture and cooking utensils. The boxes, in addition to clothes and drapery of all descriptions, contained carpenters’ tools, such as adzes, tomahawks, chisels, gimblets, hand-saws, butchers’ knives; rifles, double-barrelled guns, ammunition.”

Since 2018, as a fulltime researcher living on the Sunshine Coast, Dillon has written book after book. At present there is probably no researcher in an Australian university who can equal his knowledge on this vital set of topics. One reason for his success is that he has not only resurrected a collection of key witnesses – islanders themselves, sugar-cane growers, missionaries, sea captains, British naval officers, and politicians – but also cross-examined them with a barrister’s skill. Book available from sales@connorcourt.com

Queensland Native Police The Final Years

In 2018, I published Frederick Walker: Commandant of the Native Police,[1] which covered the history of the northern native police from their inception in 1848 to the dismissal of Walker in 1855. In 2020, I published Queensland Native Police The First Twenty Years. This book covered the period 1855 to 1879 and dealt with the complete history of the native police within that timeframe. In the course of researching the subject, it became apparent to me that Queensland’s indigenous colonial history was not one-dimensional and that eulogising the heroic struggle of indigenes for national liberation and land rights while denouncing the invasion by imperialist forces and its local servants in the same breath, was not a true narrative of the historical development of colonial Queensland. The emphasis on pastoral expansion in Queensland with its alleged attendant effect of indigenous insurgency was, even if true, not the full picture. Because the evil colonists expanded into the surrounding seas, waterways and islands thus impacting other disparate groups of indigenes. Moreover, the evil colonisers not satisfied with their local blacks, imported a whole new race of natives, South Sea Islanders, to preform slave labour on their sugar plantations.[2]

Consequently, I was sidetracked as I set about exploring these issues. Since 2020, I have published Bêche-de-mer and the Binghis, 2022,[3] Dispela Kantri Bilong Mi, Nau! Queensland Annexes New Guinea, 2023,[4] and Kanaka Boats is A-Comin’ Pacific Island Labourers in Queensland, 2023. Having endeavoured to understand the colonial history of Queensland relating to indigenous groups who were part of the development of the colony, I then turned to completing the history of the Queensland Native Police. Based on my research, the history of the Queensland Native Police cannot be told in a single tome. The subject is a vast array of intricate pathways leading to all aspects of colonial life. Where ever the settler went, eventually, he would interact with an indigene in some form or other. This would invariably lead to situations of conflict from the very real lack of understanding between the parties, coupled with, on occasion, the unscrupulous greed of each party to take advantage of the other. The result of which would end in serious personal injury or crippling property damage. With the expectations of the settler not being realised, the government would be accused of failing the settler community and, consequently, traditional methods of control and regulation would be introduced. To portray this endless series of events, together with their attendant interventions and inquiries, is impossible within the scope of a single volume.

The reader should read Bêche-de-mer and the Binghis in conjunction with this book, as I have excluded from the narrative any material relating to the maritime frontier. Where I felt it was necessary to refer to events on the maritime frontier, I have provided the appropriate citation. All of my writings on Queensland colonial history relate to the Queensland Native Police. Therefore, the reader is encouraged to refer to them out of interest or the need to clarify an issue. Furthermore, the research arising from the compilation of this book reinforces my approach and conclusions reached in my earlier books and I take this opportunity to reaffirm all my earlier books.

It is as well to remind the reader that the timeframe is nineteenth-century colonial Queensland and although firearms, and communication and transport infrastructure had made significant advances in technology such as breach loading and repeating rifles, steam engines, railways and the telegraph, the colony remained undeveloped and sparsely populated with significant numbers of uncontacted tribal Aboriginals still occupying areas of the colony. Even at this early stage of political growth, the colony was divided between the north and the southeast metropolitan region. This dichotomy shaped the outlook of how the colony was viewed and governed. The colony was described as settled or unsettled. Aboriginals were viewed as degenerate pariahs on the outskirts of southern towns while in the north, as hostile, treacherous blacks. The police were divided into a white force to protect and supervise the white population and a force of indigenous sepoys under white officers to control and regulate the wild blacks of the unsettled districts of the north and west. Furthermore, these black sepoys were eventually divided into two groups known as troopers and trackers. Ultimately, the euphemism tracker was adopted across the board to avoid any connotation of violence towards Aboriginals. However, trackers were employed purely for their skills in bushcraft[5] and for tracking lost persons or criminals on the run. In some respects, they could form a separate study, but the limitation of space precluded their inclusion in the book.

[1] Frederick Walker: Commandant of the Native Police, Paul Dillon, Connor Court Publishing, Brisbane 2018.

[2] So, the Comintern says. See Reynolds, Loos, Saunders, Evans, Richards, Bottoms, Burke et al.

[3] The History of Bêche-de-mer Fishing in Queensland Waters and Adjacent Islands, Paul Dillon, Connor Court Publishing, Brisbane 2023 (an abridged edition).

[4] Queensland’s Contribution to the Development of British New Guinea, Paul Dillon, Connor Court Publishing, Brisbane 2023 (an abridged edition).

[5] Such as fire making, foraging food and water, shelter making, general navigation, and horse finding and catching.

Queensland’s Contribution to the Development of British New Guinea.

Dillon’s latest book investigates, with keen attention to detail, colonial Queensland’s role in the development of British New Guinea. It reveals the rising importance of Torres Strait and its international steamship traffic, the contest with Germany in 1883 for the easterly or non-Dutch portion of New Guinea and the attractive islands of New Britain and New Ireland. Without the determination of Queensland, Britain would never have set up a government house at Port Moresby in 1888. Dillon reminds us that, in the eyes of some major politicians, the nearer parts of New Guinea were almost as essential as Tasmania. In essence, “New Guinea and the adjacent groups of Pacific Islands must form part of the future Australian nation.”

It is especially Dillon’s skill in weighing evidence, and in cross-examining long-dead witnesses, that makes him a historian worth reading. That he ventures into new territory is a bonus.

— Geoffrey Blainey, from the Foreword.

Paul Dillon is a Sunshine Coast based author of Frederick Walker, Commandant of the Native Police and many other titles. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from the Australian National University. Paul joined the Commonwealth Public Service in 1965. On 23 May 1986, he was called to the Bar of New South Wales and practised as a barrister in the Criminal Division of the superior courts of Queensland as counsel for

the defence.

Available from Connor Court Publishing @ $29.95. Contact: sales@connorcourt.com